- Home

- E. T. A. Hoffmann

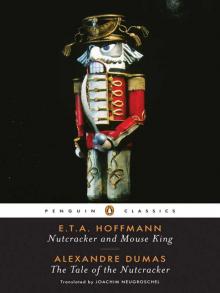

Nutcracker and Mouse King and The Tale of the Nutcracker

Nutcracker and Mouse King and The Tale of the Nutcracker Read online

NUTCRACKER AND MOUSE KING THE TALE OF THE NUTCRACKER

E. T. A. HOFFMANN was born in Königsberg on January 24, 1776, and baptized Ernst Theodor Wilhelm Hoffmann; he later substituted Amadeus for Wilhelm out of admiration for Mozart. Having studied law, he entered the Prussian civil service and held a number of legal posts in the eastern Prussian provinces. His earliest ambition was to be a composer or a graphic artist and painter, and it was not until he was in his thirties that he turned to fiction, becoming one of the best-known and most influential authors of his time. Phantasiestücke, his earliest collection of tales, appeared in 1814. This was followed three years later by Nachtstücke and then in 1819–21 by Die Serapions brüder. Among his longer works is his second and final novel, Die Lebensansichten des Katers Murr (1820–22, The Life and Opinions of the Tomcat Murr), which represents the high point of his art. He exploited the grotesque and the bizarre in a manner unmatched by any other Romantic writer. Hoffmann died in Berlin on June 25, 1822.

ALEXANDRE DUMAS was born in 1802 to a Revolutionary army general who was the illegitimate son of a marquis. In 1839, after twenty successful years as a playwright, Dumas began to focus on historical novels. During his most productive period, from 1841 to 1850, he wrote forty-one novels, twenty-three plays, seven historical novels, and a dozen travel books. Though his books were well received throughout his lifetime, he died in comparative obscurity on December 5, 1870.

JOACHIM NEUGROSCHEL has translated numerous books from French, German, Italian, Russian, and Yiddish. He has won three PEN translation awards and the French-American translation prize. He has translated Thomas Mann, Herman Hesse, and Leopold von Sacher-Masoch. He has also compiled several anthologies including Great Tales of Jewish Fantasy and the Occult, A Dybbuk and Other Tales of the Supernatural, and The Golem: A New Translation of the Classic Play and Selected Short Stories.

JACK ZIPES is a professor of German at the University of Minnesota. A specialist in folklore, fairy tales, and children’s literature, he has written several books of criticism and edited numerous anthologies. His Penguin publications include the anthology Spells of Enchantment: The Wondrous Fairy Tales of Western Culture and the Penguin Classics editions of The Wonderful World of Oz (an omnibus comprising The Wizard of Oz, The Emerald City of Oz, and Glinda of Oz) and Pinocchio.

E. T. A. HOFFMANN

Nutcracker and Mouse King

ALEXANDRE DUMAS

The Tale of the Nutcracker

Translated byJOACHIM NEUGROSCHEL

Introduction byJACK ZIPES

PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A. • Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.) • Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R ORL, England • Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd) • Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd) • Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi–110 017, India • Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore, Auckland 0745, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd.) • Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices:

80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

This translation first published in Penguin Books 2007

Translaton copyright © Joachim Neugroschel, 2007

Introduction copyright © Jack Zipes, 2007

All rights reserved

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING IN PUBLICATION DATA

Hoffmann, E. T. A. (Ernst Theodor Amadeus), 1776–1822.

[Nussknacker und Mausekönig. English]

The nutcracker and the mouse king/E. T. A. Hoffmann. The tale of the nutcracker / Alexandre

Dumas. p. cm.—(Penguin classics)

“Translated by Joachim Neugroschel; Introduction by Jack Zipes.”

ISBN: 978-1-1012-0142-8

I. Neugroschel, Joachim. II. Dumas, Alexandre, 1802–1870. Histoire d’un casse-noisette. English. III.

Title. IV. Title: Tale of the nutcracker.

PT2361. E5N87 2007

833’.6—dc22 2006053166

Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

The scanning, uploading and distribution of this book via the Internet or via any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal and punishable by law. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted material. Your support of the author’s rights is appreciated.

Contents

Introduction byJACK ZIPES

Suggestions for Further Reading

THE NUTCRACKER

Nutcracker and Mouse King

byE. T. A. HOFFMANN

The Tale of the Nutcracker

byALEXANDRE DUMAS

Introduction

The “Merry” Dance of the Nutcracker: Discovering the World through Fairy Tales

How does a wooden nutcracker, decorated as an old-fashioned soldier, manage to conquer the world of ballet during Christmastime in America and many other countries every year? Who created this odd nutcracker? What is the real story behind this mysterious inanimate figure that comes alive to fight a wicked mouse?

In her illuminating book “Nutcracker” Nation, Jennifer Fisher explains in great detail how an old world ballet from Russia became a modern Christmas ritual in the new world of America. Beginning with an account about the 1890 collaboration between Marius Petipa, a masterful choreographer, and Pyotr Ilich Tchaikovsky, the renowned Russian composer, she describes how Tchaikovsky unwillingly wrote the music to the choreography and libretto of Alexandre Dumas’s “L’histoire d’un casse-noisette” (“The Story of a Nutcracker,” 1845), which was an adaptation of E. T. A. Hoffmann’s more famous tale, “Der Nu?knacker und der Mausekönig” (“Nutcracker and Mouse King,” 1816). Tchaikovsky was never satisfied with the libretto by Petipa and Ivan Alexandrovitch Vsevolojsky, who had used Dumas’s sweetened version as his model, and he had major difficulties with Petipa’s choreography, which lacked cohesion. While writing the music, he took a trip to America to conduct several concerts and his sister died, causing grief and stress. Petipa took ill just as the rehearsals began, and his assistant Lev Ivanov had to assume control of the ballet and made changes in the choreography. The premiere of the ballet at the St. Petersburg Imperial Theater in 1892 received mixed reviews, and though it continued to be performed in the early part of the twentieth century throughout Europe, The Nutcracker was not all that popular with audiences or with dancers. Nor had it ever been considered a favorite of children or families. The libretto, which was already an adulteration of the tales by Dumas and Hoffmann, was often shortened, altered, and choreographed anew by the different companies that performed the ballet so that the full ballet was rarely performed.

It was not until 1944, when Willam Christensen produced the first full-length production of The Nutcracker in San Francisco, that the ball

et began to receive the attention it needed to become the classical ritual it is today. Christensen had been in touch with the brilliant Russian choreographer George Balanchine, who had advised him to stage the entire ballet in his original way; and Christensen, soon realizing its potential as a moneymaker and crowd pleaser for families, gradually began repeating it annually during the Christmas period. Balanchine followed suit in 1954 with his own unique spectacle in New York, and since that time not a winter season goes by when The Nutcracker is not performed throughout the United States and other countries in various formats. Not only has the ballet been adopted by Americans for their Christmas celebration as a ritual for middle-class audiences, especially young girls (as has Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol), but it has also been adapted for animated and live-action films, and there are numerous videocassettes and DVDs that offer recordings of live performances by famous European and American companies. All sorts of artifacts representing the wooden nutcracker have been manufactured, and the nutcracker has been transformed into a charming secular icon representing the joyful advent of the Yuletide season.

But this brief story does not reveal fully how the wooden nutcracker became so famous. There is much more to tell, for the nutcracker’s fame is not what its creator, E. T. A. Hoffmann, intended or what he might have expected from his unusual fairy tale.

A gifted musician and writer, Hoffmann certainly would have been pleased by Tchaikovsky’s music, but he might have also been disappointed if not upset by the libretto and choreography. Hoffmann sought to revolutionize the fairy-tale genre and wanted his readers to envision the world in a different light from how they normally saw it. His fairy tale was a provocation and a radical attempt to change the genre for children. Most of all he wanted to express his dissatisfaction with the neatly trimmed bourgeois conventions of his time and the overly rational and disciplinary way in which children were being raised. Indeed, it is ironic that “Nutcracker and Mouse King” has now been fully appropriated in another culture as a conventional if not “exquisite” American ballet and ritual by the middle class, drained of its irony and satirical barbs. Through most of his life Hoffmann endeavored to break with the propriety and custom of a pretentious class society. Yet, he could never fully discard his social conditioning to become the free-spirited artist he desired to become. His personal “failure,” however, led to his development as one of the most imaginative if not bizarre writers of his time, who desperately tried to transform life into art.

Hoffmann is the type of artist about whom biographers and critics have loved to build legends—or to explode legends by creating other legends. As early as 1827, Sir Walter Scott published a review of Julius Hitzig’s biography of Hoffmann entitled “On the Supernatural in Fictitious Composition,” in the Quarterly Review, in which he commented on Hoffmann’s unusual stories: “It is impossible to subject tales of this nature to criticism. They are not the visions of a poetical mind; they are scarcely even the seeming authenticity which the hallucinations of lunacy convey to the patient; they are the fevrish dreams of a light-headed patient, to which, though they may sometimes excite by their peculiarity, or surprise by their oddity, we never feel disposed to yield more than a momentary attention.” Scott condemns Hoffmann largely on the basis of reading Hitzig’s biography without questioning his interpretation. Hitzig was, in fact, a good friend of Hoffmann, but he was also a prude and an overly serious civil servant who never fully understood Hoffmann. He criticized Hoffmann’s life on traditional moral grounds and spurred Scott to conclude that, if Hoffmann had not led such a dissolute life, he might have written supernatural stories handled with delicacy, not macabre stories that appear incredible. Like Goethe, Scott believed that Hoffmann was sick—mentally deranged—and consequently he could not approve of the grotesque and absurd elements in his stories.

It is true that Hoffmann was sick during the latter part of his life—physically sick due to atrophy of the liver that caused a slow paralysis of his body. Even here we have a legend. As late as 1966, Gabrielle Wittkop-Ménardeau continued to spread a myth about the cause of Hoffmann’s death and attributed it to his sex life and syphilis, a rumor that an Internet encyclopedia continues to spread in the twenty-first century. He is even labeled a notorious philanderer and impecunious alcoholic. But to argue that Hoffmann was mentally disturbed, sexually promiscuous, and immoral is to overlook the fact that Hoffmann was a responsible civil servant and judge for a good part of his life, that he was an aspiring and diligent opera conductor in Bamberg, Leipzig, and Dresden, and that he was respected by some of the great minds of his time—doctors, judges, poets, actors, musicians, and administrators. Hoffmann was by no means a saint: he was overly fond of wine and may have had an affair after his marriage. But he was certainly not the demented eccentric that biographers try to make him out to be. He was a profound thinker, avant-garde in all that he attempted, and hence suspect in the eyes of the establishment, and especially in the eyes of the “philistines.” This was a common term that Hoffmann and many others at that time used to describe those people who approached life with a utilitarian and rationalistic mentality, who followed life according to arbitrary precepts, and who had a narrow if not uninformed appreciation of the arts. In short, they were superficial and pretentious people who lacked any true appreciation of the imagination and the arts. Hoffmann detested the utilitarian nature of the philistines and mocked them in his tales whenever he could. His concepts of insanity, genius, music, hypnotism, dream, and reality formed a modern aesthetic theory, and he explored his unique ideas in other worlds that, he insisted, could be found in everyone’s imagination. The discovery of these worlds, so he thought, could open up new vistas that would enable people to gain a deeper pleasure of reality. Hoffmann was a man ahead of his time, an amoral man, an aesthete, but not a man without a sense of justice. As a matter of fact, his ideas of society and justice were so fine and idealistic that his experience with real society and justice as an expert in legal affairs and as judge and counselor “sickened” him and engendered the duality in his life that he recorded in his writings—Hoffmann longed to live his life primarily for art, and he could barely tolerate the banal conditions, morals, and ethics of the social and political order that he virtually served as a civil servant. He led a double life and created the Doppelgänger, or double, so that he might resolve the split he corporeally experienced. Hoffmann dreamed of an earthly paradise, a utopia, a millennium, in which man as Homo ludens might create (free from repression) the kind of happiness we associate with beauty and the sublime. The man who risks his life for the sublime in an age of banality—this is how Hoffmann tried to realize his own life and art.

Let us try to counter some of the legends from the beginning: Hoffmann drank but he was not an alcoholic. He enjoyed wine and champagne and consumed alcohol in abundance, but we have no proof that he wrote under the influence. In fact, his stories and novels are so complicated that they demanded great concentration on his part and the full use of his conscious powers as a writer. Hoffmann easily became infatuated with young innocent women, but he rarely if ever had an extramarital affair. In his writings women represented the ideal priestess or goddess of the arts, and he idealized young women. As a talented writer, musician, and painter, he lived for the arts not for sex. Though he spoke his mind and loved to play pranks, Hoffmann was a true friend and never betrayed anyone or committed a crime. In fact, as judge, he came to the rescue of numerous people who were charged with crimes by corrupt politicians.

Hoffmann was born on January 24, 1776, in Königsberg (now Russian Kaliningrad), a city of some forty thousand inhabitants. His father, Christoph Ludwig Hoffmann, and mother, Luisa Albertine Doerffer, were cousins. His father was a lawyer, somewhat eccentric and imaginative and unreliable as a breadwinner. His mother was orderly and anxious and lacked confidence in herself. Before Hoffmann was born, his parents had two other sons. One died, and the second was taken away by the father when he separated from his wife in 1779 a

nd moved to another city. Thereafter, Hoffmann’s father and brother disappeared completely from his life. Perhaps this is why friendship and the father figure, often portrayed as an omniscient adviser or devil’s emissary, play such important roles in his writings. This may also be why Hoffmann had such a disdain for the orderly philistine life, which seemed to threaten his well-being and his artistic and imaginative pursuits.

After his father’s separation from his mother, she returned to her family home run by her dominating widowed mother, two strange aunts, and an incompetent uncle. She virtually abandoned her son to her own mother’s care and did not develop an affectionate relationship with Hoffmann. (Hoffmann made no mention of her or his father in his diaries or letters when they died during the 1790s.) The Doerffer household was a respectable middle-class family that had fallen on hard times, and Hoffmann was raised strictly with a view to making him into a lawyer or civil servant who might restore the standing of the family. As was the custom during this time, he was provided with music lessons and was expected to be well versed in all the arts. His modes of dress, speech, and behavior were governed by set social rules, which his pedantic uncle tried to enforce, and Hoffmann was constantly obliged to comply with social and familial precepts. At the same time, he was aware of the shortcomings of the odd household of domineering women and a foolish dogmatic uncle and found ways to subvert their plans to regulate his life. Very early Hoffmann came to resent and criticize the Doerffer family and sought an escape through music and writing. During his teenage years he formed a strong bond with a fellow student named Theodor Hippel and shared all his intimate dreams with him. Together they conceived numerous artistic projects and planned adventurous trips and other outings. However, their paths diverged by the time they began attending the university. Hippel, whose family was very wealthy and had been granted nobility in 1790, followed a straight and “normal” path through the university to become a civil servant, administrator, and politician with a good deal of power. As the friends grew older, he often interceded on Hoffmann’s behalf, lent him money, and tried to “stabilize” his life by giving sound advice. But it was to no avail.

_preview.jpg) Weird Tales. Vol. I (of 2)

Weird Tales. Vol. I (of 2)_preview.jpg) Weird Tales, Vol. II (of 2)

Weird Tales, Vol. II (of 2) The Best Tales of Hoffmann

The Best Tales of Hoffmann The Life and Opinions of the Tomcat Murr

The Life and Opinions of the Tomcat Murr Nutcracker and Mouse King and The Tale of the Nutcracker

Nutcracker and Mouse King and The Tale of the Nutcracker The Sandman

The Sandman